How should cities cope with a housing shortage?

Cities serve as economic engines and there is a clear link between a shortage of housing and the long-term competitiveness of entire countries.

24 OCTOBER 2023

▪ 4 Min read

In Sweden, several factors have brought construction projects in the residential real estate sector to a halt. As a result, the country’s entire long-term growth is threatened. If building new housing is not stimulated and people cannot find reasonable housing solutions in cities, they will seek job or educational opportunities elsewhere.

Major cities like Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö boast a high concentration of job opportunities and educational resources, making them economic powerhouses and attractive destinations for people to move to. This creates a higher density of people and businesses, often leading to greater innovation and economic growth. Cities also provide a diversified economy with a variety of sectors, from technology to healthcare and services, making them less vulnerable to economic fluctuations. The Stockholm region alone holds more than half of the country's total property value.

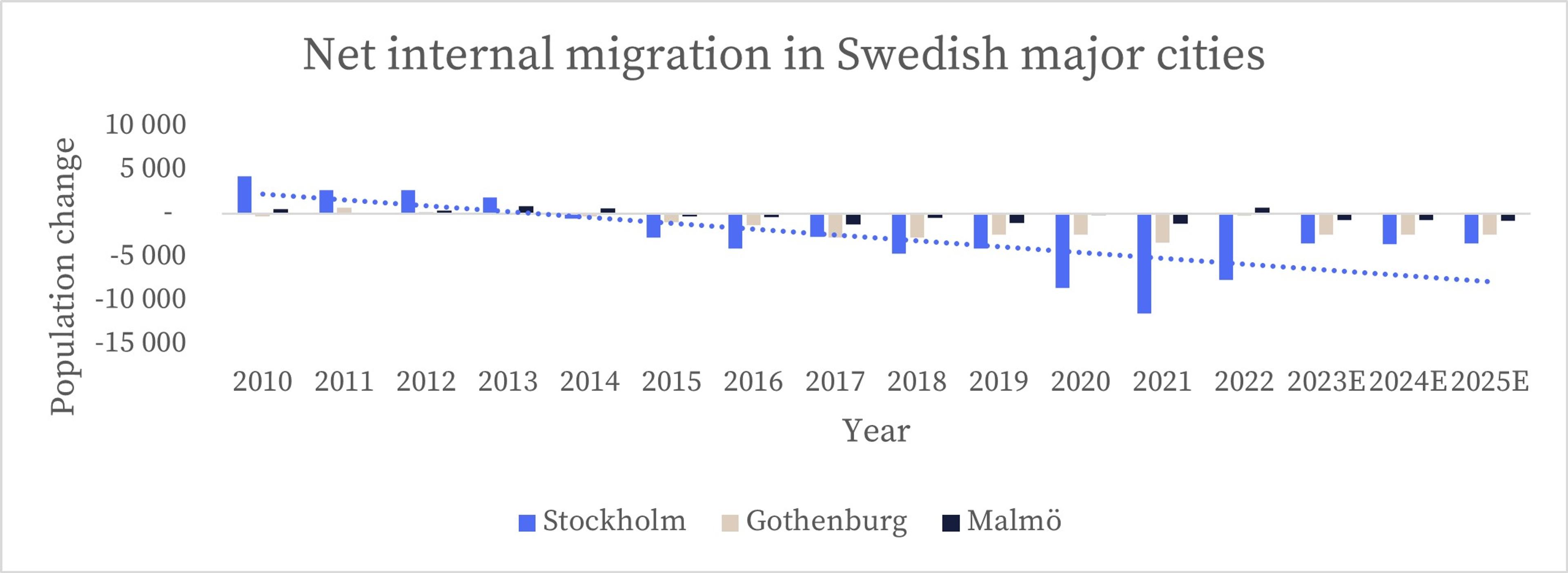

However, the immediate housing shortage makes it difficult for people to find affordable housing, which can lead to people leaving cities where there are actual job opportunities, see diagram below. The diagram shows how net internal migration has turned negative in Swedish major cities, with more and more people instead moving to regional cities – a trend which was further exacerbated by the pandemic. The housing shortage can reduce the city’s ability to attract and retain talent, which in turn undermines the city’s competitiveness both nationally and internationally. If people are forced to leave cities due to housing shortages, unbalanced economic growth can be a result, with some regions becoming impoverished while others become overcrowded. Underlining this trend, Sweden has a much lower number of student housing units per capita than the UK; about half as many (0.25 homes per student vs. closer to 0.5). This can lead to Swedish students lacking the same flexibility as those elsewhere.

Today there are extremely low vacancy levels in major cities, about 0.5%, which essentially is less than even basic relocation vacancy. Currently construction of only about 15,000 homes is likely to start this year, compared to 60,000 per year in recent years.

So, what needs to be done?

- A more efficient and faster planning and authorisation process for new housing would make it easier to build and mitigate the housing shortage.

- Financial incentives such as state and municipal subsidies could be necessary. This can include tax breaks, subsidised loans or grants. With rising construction and financing costs, developers struggle to maintain profitability. Risks of housing construction are still perceived to be too high, although land prices have fallen.

- Infrastructure investment to expand housing options is also required. Investment into public transport increases accessibility and allows people to live further away, while being able to conveniently commute to their workplace. This can increase the attractiveness of more remote areas and enable the establishment of new neighbourhoods.

The conclusion is clear: More housing is needed, and the longer there are no policy changes, the more unsustainable the situation becomes. The government needs to act now to enable more housing.

Latest articles

Get the latest insights right in your inbox

Sign up to get updates and relevant insights from Newsec. We won't be in touch more often than necessary.